Note: to understand this post, you don’t need to know anything about chess; I’ll explain everything necessary right here.

One of the best ways for a chess beginner to improve is to study king and pawn endgames, and one of the best ways to do that is to play a game with only kings and pawns. Just remove all the rest of the pieces, and have at it.

Unfortunately, while Chess with just kings and pawns is not trivial, as you improve you will eventually outgrow it, because between two good chess players, the game is very likely to end in a draw.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, my son Adam likes to design games, and he designed this very clever variant of the King and Pawn endgame that eliminates the possibility of a draw.

Rules:

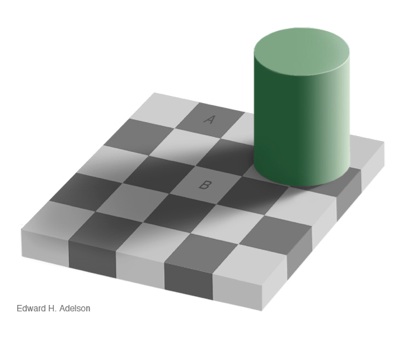

Set up the pieces as above, with four pawns plus a King for both White and Black.

The players alternate moves, starting with White.

The pawns move as in chess: one square forward, or optionally two squares forward if they haven’t moved yet, and they capture a piece one square ahead of them diagonally.

Pawns may still capture en passant as in Chess, which means the following. If an enemy pawn moves two squares forward, and one of your pawns could have captured it if it had only moved one square forward, you may capture that pawn as if it had only moved one square forward, but only if you do so with your pawn on the turn immediately after the enemy pawn moves.

The Kings can only move one square up or down, or left or right; they cannot move diagonally. (Such limited versions of Kings are sometimes called “Dukes;” hence the title of this post.)

You win the game immediately if you capture the opponent’s King, or if one of your pawns reaches the other side of the board.

You must always move; if you cannot make a legal move, you lose the game. (This is different from Chess, where stalemate is a draw.)

You may not make a move which recreates a position that has previously occurred during the game. (This is also different from Chess, but such a rule exists in Shogi, the Japanese version of Chess.)

That’s all the rules. In this game, draws are impossible, even if only two Kings remain on the board. For example, imagine that the White King is on a1, and the Black King is on b2. If White is to move, he loses, because he must move to a2 or b1, when Black can capture his King. But if Black is to move, he must retreat to the north-east, when White will follow him, until Black eventually reaches h8 and has no more retreat.

So arranging that your opponent is to move if the two Kings are placed on squares of the same color (if there are no pawn moves) is the key to victory. This concept, known as the “opposition,” is also very important in ordinary Chess King and pawn endgames, which is why skill at chess will translate into skill in this variant, and why improving your play at this variant will improve your Chess. Of course, the pawns are there, and they complicate things enormously!

Naturally, one can consider other starting positions, with different numbers of pawns.

This game can be analyzed using the methods of Combinatorial Game Theory (CGT). Noam Elkies, the Harvard mathematician, has written a superb article on the application of CGT to ordinary chess endgames, but it required great cleverness for him to find positions for which CGT could be applied; with this variant, the application of CGT should be much easier.